Edward Chapman (1911) and Andrew Nugee (1914) had their first experience of Magdalen before they were wounded, but both returned to the College after the war with only one eye. Nugee came up from Radley in 1914 as a Commoner, but on 19th November enrolled in the 9th Rifle Brigade. On 20th July 1915, serving on the Ypres Salient, he was hit by a shell which left fragments all over his body from his arms to the top of his mouth: his right eye was destroyed, the top of his nose was shattered, and the sight in his left eye severely diminished. By 1st August he was briefly in the care of the Duchess of Westminster, who had converted her chateau at Le Touquet into a hospital, and insisted that the nurses, all friends of hers, dressed for dinner to ‘cheer up the men’; Andrew, sadly, would not have been able to see either the décolletage or the tiaras.

Chapman (always known as ‘Bill’) who had matriculated from Monkton Combe as a demy in medicine in 1911, spent three months studying chemistry in Tübingen in 1913. In June 1914, he was photographed with the rest of his year, leaning nonchalantly against one of the pillars of Cloisters, a glimpse of a world so soon to be blown apart. In 1915 Chapman completed his BA in Natural Sciences at Magdalen. He joined the Royal Fusiliers, and received his commission on 28 December 1915. He arrived in France on 28 May 1916, and survived, but never forgot, the Battle of the Somme. On 20 May 1917 on the Hindenburg Line, a machine gun bullet passed between his spectacles and his brain, mercifully leaving both undamaged but taking out his left eye. Chapman’s letters to his mother and sisters (his father had just died), now in the Imperial War Museum, contain fascinating glimpses of life at the Front.

In one letter of November 1916 he recalls the voluntary surrender of four Germans, and how he had so enjoyed talking to them in the German he had polished at Tübingen that he ‘quite forgot we were in the trenches and very close to the Germans. War is so very strange and stupid when the people who do the fighting do not hate each other at all’. In another, only months before he was wounded, he notes that ‘The feeling of comradeship out here is a thing I have never experienced before. Social distinctions and so on do not count for very much when you are under fire.’ In February 1917 he writes to his mother that: ‘I sadly lack the “offensive spirit”. If all were like me, we should never win this war. Incidentally, if all were like me there would never have been a war at all!’ By the end of February, when he is an acting Captain, he is writing to his mother that ‘The more I see of shell, rifle grenades, etc, the less I like them, and the more I funk them! So I am delighted at the prospect of getting back to civilisation again for a time.’ At Easter 1917, he tells her how ‘very jolly’ it is to ride his black pony in front of the company he ‘loves’ with the ‘regimental band playing’ as they march through ‘ripping country’ from Doullens to Arras. On 1st May he is writing that ‘I am longing to be back home again. I am sick of trenches and barbed wire and shells, and the sight of desolation and death. But I am very happy out here as a rule.’ He was wounded on 20th May, and his batman returned his spectacles intact, noting the admiring affection in which his leadership and courage were held by “C” Company of the 20th Royal Fusiliers.

Nugee, after a spell at Regent’s Park, the headquarters of the newly founded Blind Veterans UK, decided to study for the Anglican ministry and returned to Magdalen, where he appears to have won everyone’s heart, because he was awarded the Pillsworth Exhibition and allowed to take his degree after only one year in December 1919. Earlier in the year, Chapman had also returned to resume his degree in medicine, and these two men with complementary eyes became firm friends, especially as Chapman changed the dressing on Nugee’s eye and nose twice a day. It must have been a very different college from the one where, in June 1914, Chapman was photographed in the same cohort as the Prince of Wales; they cannot have been the only badly wounded men in Magdalen, but even in post-war Oxford, they must have been a remarkable sight as they walked through Cloisters or sauntered round Addison’s Walk. Certainly, in later life each wore a black patch over his damaged eye.

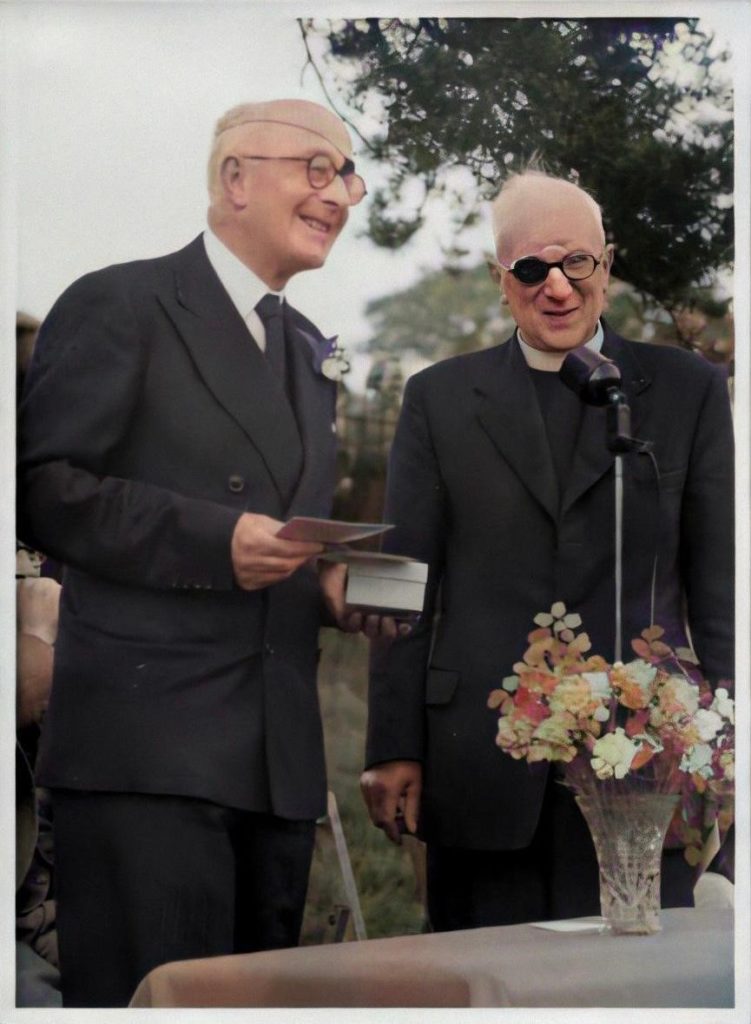

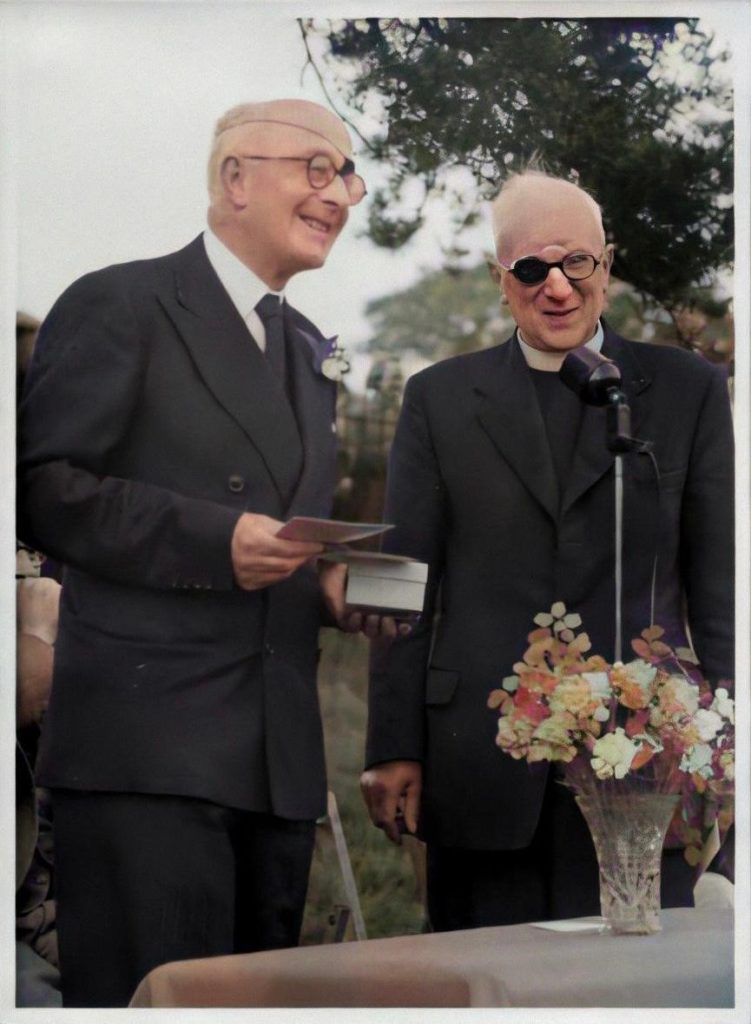

What is extraordinary is that their intersecting lives did not end there. Andrew Nugee was in a bad way when he returned from France and was nursed back to health by Elizabeth Walls of Boothby Hall, Lincolnshire. His eyesight remained very poor, but he fell in love with her and married her as soon as he was ordained in 1920, taking up his first curacy in Winchester in 1921. The Nugees had no children of their own, but Elizabeth’s eldest sister, Kathleen, was married to John Norval Home, who belonged to the legendary Calcutta Light Horse in 1916. Five years later, in 1921, he returned from India, suffering from tuberculosis, and died three months after the birth of his son, Douglas Home. When Kathleen also died of asthma, two very young children, Jane and Douglas, were left without parents. Elizabeth and Andrew Nugee adopted the two orphans, a decision which would have momentous consequences. After a succession of parishes, including responsibility for St Dunstan’s College for blinded members of the forces during the Second War, he was appointed, in 1946, Vicar of Crowthorne, Berkshire. Here, quite by chance, Edward Chapman had been practising as a doctor since 1929. When Chapman saw that Andrew Nugee had arrived in the Vicarage nearby, he greeted him with a note and hung a brace of pheasants on the large knob of the vicarage door. These two Magdalen contemporaries then served in the same parish as vicar and doctor till 1958 when Chapman retired; a wonderful photograph of the two men, each with a black patch on a different eye, survives from the retirement party. Nugee retired two years later, and his wife Elizabeth died in 1963.

Douglas Home, meanwhile, whom the Chapman family always knew as the ‘Nugee nephew’, had just begun to read History at Pembroke College, Cambridge, when the Second War began. He left Cambridge and, after being commissioned in the 1st Indian Anti-Tank Regiment in Bangalore, served at El Alamein and in Burma, where as a result of the appalling jungle conditions, he contracted tuberculosis, like his father, and ended the Second War, like his uncle in the First, in hospital. He completed his shortened degree course at Cambridge, but was invalided out of the army. During convalescence, he used to come to visit his uncle Andrew, perhaps more often than Frank Churchill in Emma.

Still very thin and not very strong he came, one day in 1947, to Chapman’s surgery to get a medical certificate to say he was now well enough to rejoin the Army. On his desk in the surgery was a photograph of a pretty young girl, his daughter Mary. Douglas plucked up courage to ask her out, took her sailing, and he and Mary married in 1949, celebrating their Golden Wedding in 1999. From their four children have sprung twelve grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren. Douglas died in 2017, but Mary is still going strong at 92. Two miraculous survivals by an incredible gift of fortuna felix (or Providence) have borne fruit in three generations.

Richard Chapman, Edward’s son (C 1947), served on minesweepers in the Royal Navy during the last two years of the Second War, and after many letters from a father determined to get his son into his old College, was finally accepted (thanks to Colin Hardie, a figure familiar to many Magdalen men), and came up to Magdalen in April 1947 to read Natural Sciences, Geology. Ex-servicemen were allowed to miss the first year and go straight into the Honours School. Since T. S. R. Boase was the President, and Dr James Griffiths, the Dean of Arts, and since both bachelors generously entertained the undergraduates, recognising their greater maturity, these men had a wonderful time. Dick Chapman successfully captained the Magdalen Golf team, joined the University Mountaineering Club, and went on many field trips with J. A. Douglas, the Professor of Geology and Mineralogy, a notoriously bad driver, and Major Sandford (as he liked to be called), the Reader in Geology, an expert on water in the desert, who had worked with the Long Range Desert Group during the war. After graduation in 1949, Dick joined Shell and wrote several books on petroleum geology. For him, Magdalen was definitely a more entertaining experience than for his father’s generation.

The story of Bill Chapman and Andrew Nugee is a reminder that the monuments in Cloisters to those who died in the two wars record only a fraction of the suffering inflicted. Magdalen played a key role in a story of friendship and courage in adversity which bore fruit in both a lifelong devotion to the college and a happy and romantic ending for both families.

By Gerard Kilroy (1967)