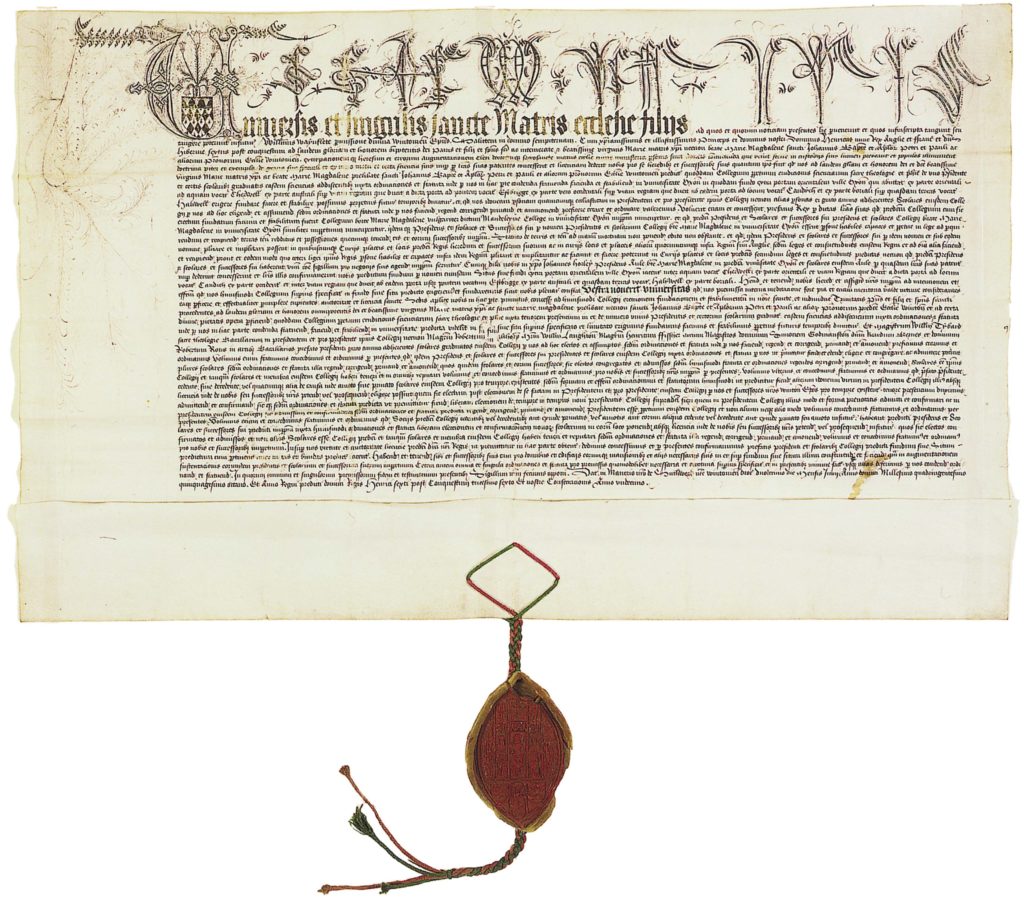

Magdalen College was founded in 1458 by William Waynflete, Bishop of Winchester, and Lord Chancellor. He wanted a college on the grandest scale, and his foundation was the largest in Oxford, with 40 Fellows, 30 scholars (known at Magdalen as Demies), and a large choir for his Chapel. Waynflete lived to a great age, dying in 1486, by which time Magdalen was equipped with a large income, splendid buildings, and a set of statutes.

Magdalen quickly became one of Oxford’s most prominent colleges. Kings and Princes visited us, including Edward IV, Richard III and James I. We soon produced alumni who achieved great things in later life, including Thomas Wolsey, Fellow here in the 1490s, and Henry VIII’s chief minister for two decades.

The College survived the troubles of the Reformation in the 16th century. During the English Civil War of the 1640s, we were solidly Royalist, and had to endure a purge of our President and many of our Fellows after the victory of the Parliamentarians.

The most dramatic period in Magdalen’s history came during the reign of James II. In 1687, our President died, and James tried twice to force the Fellows to accept a President of his choosing. The Fellows refused, and James, losing patience, demanded that all the Fellows who opposed him be expelled. This act caused national outrage: the courage of the Fellows was praised, and the King was much criticised. Late in 1688, James reinstated the expelled Fellows, but it was too late to save him: he was deposed a few weeks later.

The 18th century was not Magdalen’s finest hour. The College grew slack and complacent, and Edward Gibbon notoriously hated his time here in the 1750s. For many, the symbol of Georgian Magdalen was Martin Routh, President for 63 years, who died in 1854 at the age of 99, and who wore a wig and knee-britches in the Georgian manner to the end of his days.

Nevertheless, there were important scholars at Magdalen in the early 19th century, including Routh himself, Charles Daubeny, Magdalen’s first modern scientist, who successfully fought for the creation of an honours school in Natural Science at Oxford in 1850, and John Bloxam, the College’s first historian, who reinvented Magdalen’s May Morning in its current form.

The College revived under Routh’s successors, Frederick Bulley and Sir Herbert Warren, especially the latter with the then Prince of Wales (later Edward VIII), coming up in 1912. With the support of Bulley and Warren, the Chapel Choir also improved greatly, attaining the national reputation which it holds today.

The 20th century has seen Magdalen’s academic reputation flourish. Two of our most famous Fellows from this period were the English scholar and theologian C.S. Lewis and the historian A.J.P. Taylor; in addition, ten Nobel Prize winners have been Fellows or students here. Women first came here in 1979, and the College today prides itself on being an inclusive institution, open to all.

When William Waynflete founded Magdalen College in 1458, he inherited all the buildings of the Hospital of St John which stood on this site. The political troubles of the next few years delayed any plans for the redevelopment of the site, and so the earliest members of Magdalen presumably occupied the Hospital’s buildings.

Finally, in 1467, work began on the wall, now known as Longwall, which circled the whole of the site of Magdalen, and in 1474 work began on the Cloisters, with their Chapel, Hall and Library. These were largely finished by 1480. The mason employed was William Orchard, who also worked on the Divinity Schools. The only major portions of the Hospital to survive were part of the High Street range and its Hall, converted into a Kitchen.

Waynflete and Orchard planned a College on the grandest scale, but several important additions were made after Waynflete’s death in 1486. In 1492, work began on a splendid bell tower, 144 feet high, which was ready for use by 1505. Other major work from this time was the completion of the High Street range, to link the Tower with existing buildings, and, in 1508/9, the erection of the large allegorical gargoyles in the Cloister known as the ‘hieroglyphics’.

Other buildings, now lost or replaced, were erected at this time, including the earliest President’s Lodgings, and the first home of Magdalen College School. The latter building, which also housed Magdalen Hall (now Hertford College), was badly damaged by fire in 1821, and its only extant fragment is the so-called Grammar Hall. Little major architectural activity then took place until 1635, when the Kitchen Staircase was added.

In the late 1720s, Edward Butler, the then President, planned to replace most of the Cloisters with a grand new quadrangle in the Palladian style, and commissioned Edward Holdsworth to design it. Work started in 1733 on what would have been the north range of this new quadrangle, but after this range was finished by the end of the decade. the project went no further, presumably due to a lack of energy and funding.

In the 1820s and 1830s the College saw a major rebuilding programme, precipitated by an unwise decision, swiftly reversed, to demolish the north side of the Cloisters. The Cloisters were restored, the Chapel refitted, and the Grammar Hall made good. Meanwhile, in 1847 Charles Daubeny, Magdalen’s first great scientist, built a laboratory across the road—the first laboratory administered by a College, and now the only one to survive—and in 1849–51 the College built a new Hall for Magdalen College School.

In the 1880s George Frederick Bodley and Thomas Garner carried out several projects at Magdalen, namely St. Swithun’s Quadrangle, a new President’s Lodgings, and a gate from High Street. St. Swithun’s Quadrangle was left half-completed, but in 1928–31 Giles Gilbert Scott finished the work, creating Longwall Quadrangle, and also converting Magdalen College School Hall into the College’s Library. The College’s newest buildings are the Grove Buildings (1994–9) and Holywell Ford (1994–5), designed respectively by Porphyrios Associates and RH Partnership Ltd.

Every President to govern Magdalen since its foundation is listed below. Some colourful names appear: Owen Oglethorpe, in office 1554-55, was a moderate who struggled to control Puritan students, while Accepted Frewen (1626-44) received his unusual name from the practice common in the seventeenth century of selecting a word in the Bible at random. Magdalen’s longest-serving President is Martin Routh, who began in 1791 aged 36 and died in office in his hundredth year. Unsurprisingly, he had a reputation for taking things slowly. Some Presidents, in contrast, had very short tenures. Samuel Parker (1687-88) and Bonaventure Giffard (1688) were appointed directly by James II. When the Fellows refused to support these Catholic Presidents the Crown expelled them, only for a restoration to happen the following year, an event still celebrated by the College. Our current President, Dinah Rose, QC, has been in the post since September 2020.

1457-1480 William Tybard

1480-1507 Richard Mayew

1507-1516 John Claymond

1516-1525 John Higdon

1525-1528 Laurence Stubbs

1528-1536 Thomas Knollys

1536-1552 Owen Oglethorpe

1552-1554 Walter Haddon

1554-1555 Owen Oglethorpe

1555-1558 Arthur Cole

1558-1561 Thomas Coveney

1561-1589 Laurence Humfrey

1589-1608 Nicolas Bond

1608-1610 John Harding

1610-1626 William Langton

1626-1644 Accepted Frewen

1644-1647 John Oliver

1648-1650 John Wilkinson

1650-1660 Thomas Goodwin

1660-1661 John Oliver

1661-1672 Thomas Pierce

1672-1687 Henry Clerke

1687 John Hough

1687-1688 Samuel Parker

1688 Bonaventure Giffard

1689-1701 John Hough

1701-1703 John Rogers

1703-1706 Thomas Bayley

1706-1722 Joseph Harwar

1722-1745 Edward Butler

1745-1768 Thomas Jenner

1768-1791 George Horne

1791-1854 Martin Routh

1855-1885 Frederick Bulley

1885-1928 Sir Herbert Warren

1928-1942 George Gordon

1942-1946 Sir Henry Tizard

1947-1968 Thomas Boase

1968-1979 James Griffiths

1979-1988 Keith Griffin

1988-2005 Anthony Smith

2005-2020 Sir David Clary

2020-Dinah Rose

This website provides brief but full biographies of all the members of Magdalen who were killed in or died because of the Great War. The website also considers what those members of Magdalen who were “deemed […] to have been duly enlisted in His Majesty’s regular forces”, did during the war – including those who were for whatever reason exempt from military service. The cohorts of 1912 and 1913 have been examined in some detail so that, by considering the fate of their contemporaries, we get some idea of what those killed might have achieved and what Britain lost by their deaths. Finally, we look at the opposition to the war among members of Magdalen men by studying those who were known to have been Conscientious Objectors and those who were known or thought to have been Pacifists.